~ A New Beginning ~

by jfclover

~~~

“Telegram for you, Mr. Cartwright.”

I reached into my pocket for a nickel and handed it to the young boy who’d come running toward me. “Thanks, Carl.” I started to open the envelope and then remembered the kid had become the sole support of his family after his father was killed in a mining accident. “Carl?”

“Yessir?”

I knew he wouldn’t accept charity, so I had to think fast. “Are you busy right now?

“No, sir.”

“Would you like to earn yourself a shiny new dollar?”

“A whole dollar? You bet I would.”

I reached into my pocket and pulled out three letters for Adam. “Would you have time to take these letters to the post office and give them to Mr. Oliver to mail?”

“Yessir. I sure would.”

“Okay. Here’s three cents for the letters and here’s a dollar for your trouble.”

“Thanks, Mr. Cartwright.”

“Don’t spend it all in one place, ya hear?”

“I won’t, Mr. Cartwright,” he said, fingering the shiny coin. “I don’t believe it. I never had a whole dollar before.”

I pulled the telegram from the envelope, still smiling as young Carl ran like the wind down the wooden boardwalk. I finally looked down at the small, yellow paper I held in my hand. I read it once—I read it again. “Fire—”

Pa sat behind his desk; his eyes focused on the ledgers when I flew through the front door calling his name. I started to speak and he held up his hand, signaling me to wait. “I think you’ll want to read this, Pa. It’s from San Francisco.” Pa looked up. He set his pencil down and I handed him the wire.

“`

Ben Cartwright, Ponderosa Ranch, Nevada (stop)

Fire at Collier and Cartwright (stop)

Adam is alive, Jackson missing (stop)

Recovering at Sisters of Mercy Hospital (stop)

- Collier, San Francisco (stop)

“`

“Adam—” Hoss whispered, as he stood reading over my father’s shoulder.

I leaned forward, steadying my fingertips on Pa’s desk. “I’ll leave right now, Pa. I can be there in just a few days.”

“Sit down, Joseph.”

I let out a long sigh. “What then?”

“Let’s think for a minute before any of us go running off to San Francisco.”

“What’s there to think about? Adam’s hurt.”

“I know that Joseph. Just settle down and let me think.”

I couldn’t understand why we were wasting time when Adam was injured, and as far as the severity of the fire, we had no clue. The telegram didn’t tell us enough about the situation and I was ready to ride not sit here forever figuring out what to do.

“We can’t all go,” Pa said.

“I’ll go,” I said.

“Joseph, please.”

I stared at my father knowing he’d be the one to go, leaving Hoss and me here to run the ranch. I could argue all day, but I’d lose the battle. “Enough said—end of discussion,” would be my father’s words.

Pa reread the telegram as if new and different words would stand out on the small sheet of paper. Finally, he laid it down on his desk and stood up.

“All right, Joseph, you go.”

“Me?” Surprised was an understatement. “Okay.”

“There’s a stage leaving for San Francisco tomorrow afternoon. Hoss and I will manage here while you’re gone.”

I glanced up at Hoss, who got the short end of the stick this time. Pa would be anxious and totally out of sorts until I sent word of Adam’s condition. Life for Hoss would be a definite challenge while I was gone.

I’d been shaken and bounced, knocked constantly against the inside door of the stage, and all the while, a woman’s young son cried and carried on most of the way across California. I was ready to set foot on solid ground. I exited the coach first, but Pa taught me to be a gentleman, and since I didn’t see anyone meet mother and child, I slapped a smile on my face and waited patiently so I could help the poor woman and her son off the stage. I realized she looked as tired and as miserable as I felt, so I asked if she needed help getting to a hotel or maybe I could hail a cab for her, but she said she could manage—thanked me and she and her son moved quickly across the busy cobblestone street.

I’d done my duty as a gentleman, so I picked up my satchel and asked the nearest person walking toward me where the Sisters of Mercy Hospital was located. I was surprised to find out I was only blocks away. I had planned to rent a horse but maybe I wouldn’t need one if I could secure lodging close to the hospital.

I started walking. It had been years since I’d been to San Francisco, but I do remember coming out with Pa and Hoss when I was around sixteen or seventeen years old. Pa was so protective of us boys in those days, so worried we’d end up shanghaied, and as it turned out, he ended up the one being snatched and almost sent off on a little vacation at sea. I chuckled remembering how the three of us handled the group of sailors determined to take Pa away. They’d never run into anything like the three Cartwrights or Hop Sing for that matter.

Sisters of Mercy

The sign above the double front doors confirmed I’d reached my destination. I probably should have dropped my bag at a hotel first but I was anxious to see my brother.

“Adam Cartwright?” I inquired when I reached the front desk.

“Are you a relative?”

“He’s my brother,” I answered the woman who was covered from head to toe in white.

“Right this way, Mr. Cartwright.”

The corridor was filled with people moving in both directions. I followed her down to a large room—a ward—lined with beds and filled to capacity. I saw only men in this room and figured there must be another similar ward for women. There were two rows of beds with a long center aisle. She put her finger to her lips, insisting on silence as we entered the room. With her back to me, I rolled my eyes. Did she think I’d planned a song and dance routine?

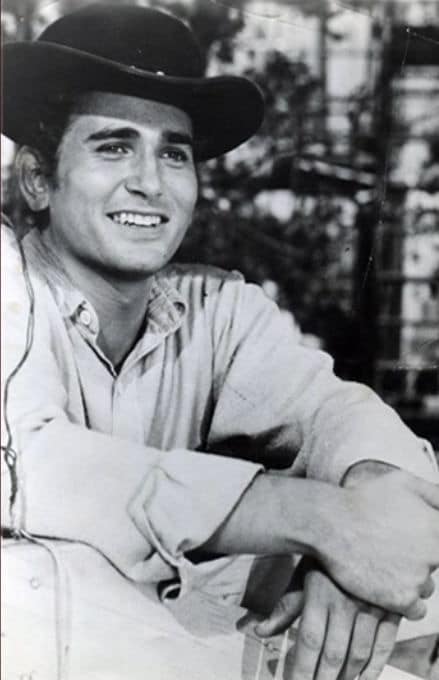

I recognized Adam halfway down the aisle. A sheet, along with a thin wool blanket, was pulled up, covering his legs and chest. Only his face and a new addition—a full beard—appeared. When we stopped at the foot of his bed, I waited for the nurse to say something, but all she did was nod her head toward my brother, who lay there sound asleep, then she quietly tiptoed back down the aisle and out of the room.

I sat my bag on the floor at the foot of the bed, laid my hat on top, then slipped in between the neatly lined beds and sat down near the foot of Adam’s. I felt like an intruder. I was the only able-bodied person in the room—no other visitors or staff members—just me.

“Adam?” I whispered, remembering her cue to keep quiet. I could make out my brother’s form, and I rested my hand lightly on his arm; he began to stir. His eyelids fluttered at first and then opened, leaving narrow slits as he studied me, although he looked unsure of whom he was seeing.

“Adam?” I said again.

“Joe? Is Pa—”

“No, just me.” His voice was weak and I wasn’t sure whether to ask questions or not. “You okay?”

I didn’t get an answer only a throaty grunt. “What the heck happened?”

“Fire—”

Adam was either exhausted or he’d been given some kind of medication. His words were heavy and forced. “I should come back later,” I said. His dark lashes fell to his cheeks as his eyes slowly closed. “Let you sleep—” I was too late. He’d already drifted off.

I picked up my hat and bag and walked quietly down the aisle of the ward then started down the long hallway, the same way I’d come in. I stopped one of the nurses, the same woman who’d guided me in. Only a portion of her face showed between the high collar and the large, white hat with wings on either side that rested just above her eyebrows.

“Excuse me, ma’am … um miss, is there a doctor I could talk to about my brother?”

She was maybe half my size but when she scrunched up her face in such a severe manner, I took a small step back, a bit frightened. “Sister,” she said.

“Oh, I’m sorry, ma’am. I mean, sister.”

“Right this way, Mr. Cartwright,” she said, shaking her head. It was the same woman, sister. She remembered my name. “Thank you,” I said.

She led me to a room not too far down the hallway. “Have a seat, Mr. Cartwright. The doctor will be here shortly. He’s just finishing rounds and he can tell you more about your brother’s condition than I’m able.”

“Thank you.”

Again, I set my bag and my hat on the floor and I sat down in the only available chair. The office was stark; white plaster walls, with only the dark, wooden desk for contrast. A diploma hung on one wall and a plaster Jesus, pale and bleeding, on another. I’d only sat there long enough to notice those things before the doctor walked into the room.

I stood and extended my hand. “Joe Cartwright, Doctor.” He was tall like Adam only blonde and fair—a young man for a doctor, maybe my age. I’d been so used to old, white-headed men, and I was taken aback at first.

“Jonathan Mills, Mr. Cartwright, glad you could come.” He shook my hand. He had a firm grip and an easygoing demeanor. “Have a seat,” he said, taking a seat behind his desk.

“Call me Joe or this could be confusing, doc.”

“All right, Joe.”

Before I could ask about Adam, a nurse walked in and handed us each a mug of coffee. I didn’t normally drink mine black, but it would have to do. I took a small sip and looked up at the doctor.

“So, what can you tell me about my brother?”

He set his cup down and leaned forward. “Your brother’s a lucky man, Mr. Cartwright.”

“How’s that?”

“He’s alive.”

He had my attention. “Was the fire that bad?”

“Practically the entire building and the building adjacent were destroyed. Your brother was lucky to get out alive.”

“And his partner, Mr. Collier?” I asked. The doctor looked down at his desk. He didn’t answer right off. I remembered the wire saying he was missing. Adam had told us early on that Jackson had a wife and a child. What would happen to them now?

“I don’t know. He wasn’t brought here.”

“I see.”

“Your brother will sleep for a while,” Mills said, looking back up at me. “I’d just given him something for pain, not knowing if, or when, a family member might arrive. My suggestion is that you visit the police station. It’s right down the block. I think they may be able to tell you more than I can about this whole situation.

“Okay—” His comment struck me as odd, but I was a visitor to the city and maybe this is how things worked. “One more question if I may. Is there a hotel close by? I could sure use a bath and a shave.”

The doctor smiled. “Yes, there is. Turn left out the front door. The Majestic is about five blocks up the hill.”

After I picked up my bag and hat from the floor, I shook the man’s hand. “When’s a good time for me to come back, Doc?”

“I’d give your brother another two or three hours. It will be time for the orderlies to serve supper and he’ll be coherent by then, long enough to eat at least, but I’ll administer his evening medication soon after he’s finished his meal.”

“I best be on my way then. Thanks for all your help.”

The Majestic was a nice enough hotel. I knew there were fancier places around the city, but this was close to the hospital, and with Pa not along, this suited me just fine. The bathwater was sent up promptly, although I didn’t have time to just lay back and soak in the steaming hot water as I wanted, I lathered up, rinsed, and got dressed. I needed to talk to the police and get back to the hospital as quickly as possible.

I was introduced to a detective, Max O’Hara, who’d been assigned to Adam’s case, and after a short greeting, he had me follow him into his office. There was no coffee served this time and I could have used a cup—I was starting to fade from the day’s events. Mr. O’Hara didn’t mess with words. He got right to the point, explaining what information he’d gathered so far.

“As of now, Mr. Cartwright, we believe the fire was an act of arson.”

“Who—who set the fire?”

“Everything points to Mr. Collier, your brother’s partner.”

Mr. O’Hara gave me a minute for the information to sink in. “Jackson Collier? Are you saying he tried to kill my brother?”

“That’s exactly right, son, although he may have had a change of heart and saved your brother’s life after all.”

“So you’re saying he knew Adam would be in the building when he set the fire?” I’d always thought Jackson and Adam were such close friends. Why in God’s name would he try to kill him?

“We think he might have set the fire and then rushed back inside to save your brother. We have a witness who thought he saw Mr. Collier running away from the building and then running back in, even though the entire structure was in flames by that time.”

“I don’t know what to say, Detective. I’m at a loss here.”

“That’s what we believe happened,” O’Hara said, although hesitantly. “Now, we have no definite proof and we haven’t been able to locate Mr. Collier as of yet. It’s just theory right now.”

“So he’s alive.”

“We think so.”

“Do you know why? Why would he?” I was missing something here. Two plus two wasn’t adding up.

“I was hoping maybe you could fill me in, Mr. Cartwright.”

“No,” I said, trying to think how this could be true. “I thought they were best friends.”

“Well, after interviewing his wife, Mrs. Annabelle Collier, we found out some pertinent information concerning her husband.”

“And—”

“She explained how distraught, how troubled he’d been since receiving a certain letter.”

“A letter? Letter from whom?”

“Well, Mr. Cartwright.” He seemed to hesitate and he stared down at the notes he had placed on his desk. All I could see was his rusty-colored hair with a touch of gray at the temples until he looked back up at me and continued. “Mrs. Collier said her husband had received a letter, maybe six months ago, from the Nevada State Prison stating that Mr. Collier’s father along with several other inmates had escaped.”

Two plus two was adding up nicely now. “Go on, Detective.”

“She told me, Mr. Collier had believed his mother and father had died some thirty years ago, an epidemic I believe, and he knew nothing about his father’s prison sentence or why he’d been sentenced until he made the necessary inquiries.”

I looked straight at O’Hara. It wasn’t too tough to figure out what was coming next. “I assume you can guess the outcome of Mr. Collier’s inquiries without me stating what his wife told me, can’t you?”

I nodded. “He knows I’m the one who killed his father. Is that what comes next?”

“That’s right, Mr. Cartwright.” He cleared his throat. “We believe he may have wanted to kill your brother to get back at you, but remember now, it’s only a theory.”

“It makes perfect sense, doesn’t it, Detective—an eye for an eye?”

“I wish I had all the answers, son. In any case, there’s always the possibility he set the fire and then had second thoughts, I mean, maybe Mr. Collier had a conscience after all.” O’Hara leaned forward over his desk. “Now, this is only speculation you understand, but if I was you, and until this man’s found and questioned,” O’Hara paused, making sure he had my attention, “I’d watch my back.”

“Thanks for the information and the warning, Detective.” I let out a deep breath. “I’m staying at The Majestic if you should find out anything more—or I could check back.” I stood up to leave. “Right now, I need to get back to the hospital and see my brother.”

“I have men canvassing the area for leads, Mr. Cartwright, and they’re on constant lookout, but as I said before, stay sharp.”

I started walking toward the hospital, and with all that had gone on today, all the new information to absorb, and then trying to figure out a way to tell Adam, I realized I’d never even asked the doctor how badly Adam had been hurt. His face looked fine but he was covered from head to toe with a blanket. I should stop somewhere and wire Pa and Hoss, but I don’t have enough information yet. It would have to wait until after my visit tonight.

When I stopped at the front desk, I noticed a young lady, a very attractive young lady, talking to the same nurse who had taken me to see Adam earlier this afternoon. I was formally introduced to Miss Abigail Collier. “You came,” she said with a smile. “I wired your family.”

All along, I thought Jackson’s wife had sent the telegram. Now I realized it was his sister. Annabelle was his wife and Abigail was his sister. If I could keep that straight, I’d be in good shape.

“It’s nice to meet you, Miss Collier,” I said. I didn’t know if she hated me as much as her brother did or not.

“Please call me Abby,” she said, in a sweet, pleasant voice.

“I will, Abby, if you’ll call me Joe.”

I turned to the nurse. “Is my brother awake?”

“The patients are being served supper, Mr. Cartwright. I would appreciate it if you and Miss Collier would wait out here and not cause extra confusion in the ward until the men have a chance to finish.”

“Is there somewhere the two of us could sit and wait?”

“Right this way.”

I glanced at Abby and smiled as the nurse marched us down the hallway to a waiting room. She seemed glad to be rid of us and anxious to get back to whatever she’d been doing before the interruption.

Abby walked in first, but I turned to the nurse with the wings on her hat. “I just wanted to thank you for your time, ma’am.”

“Sister,” she huffed.

“That’s right, Sister. My apologies again. I know how busy you must be with hospitals so understaffed and patients demanding this and that, and then to have the two of us come in a disrupt your whole routine, well, I’m—I’m grateful for people like you, who offer so much for such little reward.”

“You’re very kind, Mr. Cartwright,” she said, sporting a smile instead of a frown. “It’s a privilege to be of service to you. You just let me know if there’s anything else you need.”

“Thank you again, Sister.”

When I entered the waiting room, Miss Abigail Collier was already sitting at a small table with her hand covering her mouth. She looked up at me and a slight chuckle slipped out.

“What?” I said.

“You’re quite the charmer, aren’t you, Mr. Cartwright?”

“Joe,” I said. “Call me Joe.”

“Okay, Joe.”

“Whatever do you mean?”

“Is that how you treat all the ladies?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Coffee?”

There was a stove off to the far side of the room and a coffee pot sat on top. I took a chance that there was something warm left in the pot and poured us each a cup. I placed a mug in front of Abby and I sat down across from her, my cup still in my hand.

What should I say to her? Should I apologize for killing her father? Did her brother tell her the whole story? I was relieved when she started the conversation.

“I want to apologize for my brother not being here, Joe,” she said, after sipping the coffee. “I can only imagine how distraught he must be after hearing about the fire.”

I was caught off guard by her statement and not quite sure how to respond. “I’m sorry things turned out as they did,” I said. There was a brief silence and then she continued.

“I need to find Jackson. I need to know he’s safe. He was so upset over—I haven’t seen him since the fire and I don’t know if he’s hurt or where he’s gone.” She glanced through the doorway and then back at me. “I thought maybe Adam would know something and I came here to ask.”

Abby pulled a handkerchief from a small, drawstring bag and dabbed her watery eyes. It was obvious O’Hara hadn’t told her what he and his team suspected happened at Collier and Cartwright, and I have to assume she has no clue as to her brother’s involvement.

“Have you talked to the police, Abby?”

“Oh, no, I couldn’t. I’m—I’m just too upset over this whole ordeal. I worked there too, Joe, and now with Jackson gone and Adam hurt—and with the firm and everything in it burnt to the ground, well, all of us are out of a job, I mean, well I guess what I mean is there’s no means of support—no money coming in.” Again, she dabbed at her eyes. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t be telling my troubles to a total stranger. It’s just so—”

It may have been the wrong thing to do, but I laid my hand on her arm. “I’m sorry this is so hard for you. I’m sure your brother will turn up sooner than you think.”

“There’s more, Joe.” Again, she wiped at her eyes. I gently squeezed her arm and waited for her to say more. I wondered if she knew about the letters Jackson had received after his inquiries. Surely, she had to know. They must have discussed it at some point and I wasn’t quite sure I wanted to hear what else she might have to say. “I hate to ask—”

“Go on,” I said, taking my hand away.

“My father,” she said, “was killed, and I—did you? I mean, were you part of the posse who killed my father?”

There it was. She knew the whole story, and now she wanted to hear all the gory details of his capture or demise from me. I fidgeted with my hat under the table.

“Um—well, I wasn’t part of the posse exactly, although at the time, my father and my other brother, Hoss, were.” How could I say this? How could I tell her I was lured to a line shack, only to end up killing her father before he killed me?

“You see—when I found your father, he was hiding out in a cabin on the Ponderosa, that’s where we live, but I’m sure Adam has mentioned that.” Geez—I was rambling. I didn’t want to give this young lady the horrid details. No matter what I said to her, this man was her father, and nothing I said would matter other than the fact that he was dead and I was the reason why.

“He wore prison clothes,” I continued, “and I gathered he was an escaped convict and was hiding out, so when I entered the cabin—well, there was kind of a struggle between your father and me and—and the gun went off and—”

“I see,” she said, not wanting or needing me to finish.

I’d been stumbling for the right words, just enough to get by without telling her everything. I’d never hated a man like I’d hated Harold Collier and I figured the less said the better.

“I’m sorry it happened that way. If I could have taken him back alive, I—” Just shut up Joe. Enough said.

As soon as Adam was well, and Jackson was found and thrown behind bars for attempted murder, I would magically disappear from San Francisco and head back to the Ponderosa, leaving the Collier business behind.

Where was Jackson now and how much effort was being put forth to find him? He could be miles away, but he could also be right here in the city, waiting and watching my every move.

What would Adam do now? His partner tried to kill him, and even if I’d been the ultimate reason; it was still a difficult situation. There would be headlines and bad press, not to mention the office was gone—there’d be no more Collier and Cartwright, so what would come next? The Cartwright Firm? Would it be possible for Adam to continue?

I looked up from my musings and Abby was staring at me. “You don’t look like a murderer, Joe Cartwright.”

I swallowed hard. “Thank you. I’m not.” But if I were, I would have murdered your father ten times over.

“But you killed my father.”

“It was self-defense, Abby, the gun was between us—we struggled—it fired. Your father’s finger was on the trigger.”

“I see—”

“Do you believe me?”

“I have to, don’t I?”

“I don’t have to but it is the truth.” She looked disturbed by what I tried to say without giving up too much information.

“So did you and my father have a disagreement or—”

“A disagreement? No—he escaped from prison, Abby. He was holed up on our ranch. We struggled—the gun went off—and he was dead.”

“So are you saying you wanted my father to die?” Yes—yes—yes—more than anything else in this world, but in good conscience, I couldn’t say those words to that madman’s daughter. “Joe?”

“If it was a choice between him and me, Abby, then yes, I didn’t want to die.”

She looked away. Part of me understood her pain. If it had been my father— How could I explain? I needed to choose my words carefully. “When was the last time you saw your father?”

“I was a girl, the summer I turned ten.”

“And do you know why your father was sent to prison?”

“It’s so confusing, Joe. Jackson and I were visiting with my aunt and uncle in Boston that summer. We were told our ma and pa died from an outbreak of cholera, and then—then to hear such lies—lies about my father—I don’t know who or what to believe.”

God, would she ever believe the truth? She loved her father and maybe Jackson did too. They’d been told lies to protect them as young children, and maybe that was for the best. “Are your aunt and uncle still alive?”

“My Uncle Henry is, but Auntie Rose died years ago.”

“It might help if you wrote your uncle and asked him to tell you the truth.”

“I already know the truth, Mr. Cartwright, and I won’t believe lies about my father.”

That was up to her, I guess. She would always hate me for killing her father. That was a given. Did Jackson also think it was a lie? Did he think his father was wrongfully accused? I knew what wrongfully accused was all about but I sure wasn’t going to fill Abby or Jackson in on my prior obligation to the state of Nevada.

“Maybe we should discuss all of this another time. I need to see Adam before Dr. Mills sedates him again.”

“I came to see Adam too, Joe.”

“Well, good then. Let’s both say hello.”

I stood up and reached my hand out for Abby. Her scent and the graceful way she stood up from the chair, then rested her delicate fingers in my hand made me realize how long it had been since I’d even thought about a woman much less touched one.

This was crazy. This woman hated me, and according to what she believed, she had good reason. I tried to brush the feelings away. But were they so wrong? Was it only because I was away from Virginia City, and the watchful eyes of her citizens, that I could touch a woman without people staring and shaking their heads in disgust?

As easily as I’d held her hand only moments ago, I stepped away, letting her lead us to Adam’s ward. As I followed her down the hallway, I couldn’t help gazing at this delicate lady, whose hips moved almost sensually, bringing about the gentle swishing of crinoline under her long-pleated walking skirt. She stopped, peeked into the ward, and nodded.

Adam was sitting up in bed with a tray placed on his lap. He glanced up and saw us both coming toward him. Not that Adam’s face gave away much to begin with, and now with the full beard, I wasn’t sure if he was smiling or not.

I couldn’t help but grin as we got closer. I let Abby slip in on the left side of his bed and I moved to the right. I needed a little distance from her if I wanted to concentrate on the reason I was here. “Hello, big brother.”

“Hello yourself, little brother,” he said and then turned his head. “Abigail.”

Adam’s voice sounded raspy and raw and I didn’t know if it was wise for him to be talking or not. If he couldn’t talk or didn’t want to talk, knowing my brother as well as I did, he would stop when he needed to. “So, tell me, Adam, are you okay? I mean, what the heck happened?” I couldn’t say too much about Jackson and the fire with Abby sitting right there listening, but I did need to hear Adam’s version.

“The doctor tells me I’m healing quite nicely, considering.”

“Considering?”

“It wasn’t so much the burns, of which I have a few sensitive areas still, but it was the smoke inhalation that caused most of the doctor’s concern.”

“And—”

“And it’s my lungs, Joe. I’m breathing evenly now, much better than before. I think the big scare is over though the damage is done.”

“I’m sorry, Adam.” Adam looked up; his eyebrows knitted together and his eyes narrowed. “What?” I said.

“Were you here earlier today?”

“Yeah, but you were kind of out of it.” Adam motioned at me to take his empty tray, and all I could think to do was to set it down on the floor at the foot of the bed.

“Thanks,” he said, letting out a long breath, but then he started coughing and couldn’t seem to control the sudden attack. I tried to sit him up straighter, thinking that might help.

“You okay?”

He nodded, but the cough continued. He pointed to the tray. I scooted to the far end of the bed and grabbed the glass of water. “Here,” I said. He drank heartily and the cough finally subsided. “Better?”

“Much,” he said, nodding.

“I can come back tomorrow if you’d rather not talk tonight.”

“I’m fine now.” He patted the side of his bed. “Sit,” he said. “Talk to me.”

Adam’s words were short and to the point, and I figured he wasn’t up for a repeat performance. He wanted to hear everything about the ranch, but I would save most of that for later. I’d just throw in bits and pieces for now.

“You know how Pa is. He sent me to town every day last week to pick up mail when your scheduled letter hadn’t arrived.” Adam started to smile. “Yeah, don’t give me that look. You know exactly what I went through.” Adam nodded. “I’d sent you a couple of telegrams and heard nothing back, so I was going to have to tell Pa that something wasn’t right, and that just happened to be the day Abby’s telegram arrived.”

“You know about the fire, right?” He glanced at Abby and she nodded her head.

“Some,” I said. I wasn’t sure what Adam had been told. “How bad was it?”

“Not sure, Joe. Pulled from the fire—then here.”

“You’re a lucky man, Adam. My brother was struggling to breathe but I had to ask anyhow. “Who pulled you out?”

“Don’t know.” I wondered if Jackson had second thoughts about killing my brother although it could have easily been a city fireman or someone else who saw the fire—who knows. “Painkillers,” he said, rolling his eyes. “Not sure about anything.”

I glanced at Abby. Exactly why was she here? My brother didn’t seem excited about seeing her so that ruled out any kind of romance or close friendship between the two of them.

“I should probably let you sleep, brother.”

“Where are you staying, Little Joe?” Abby was quick to pick up on my brother’s choice of words and she looked at me quizzically.

“Little Joe?”

“Just a nickname,” I quickly added. “I’m checked in at The Majestic, Adam.”

“You can stay at my place, you know.”

“Maybe when you are released I will but for now I’ll stay put.”

I saw Doctor Mills coming our way. “Looks like you’re heading for la-la land, big brother.”

Adam began to laugh, but the cough started up immediately. I reached for the glass on the tray, but it was empty. “I’ll get more water.” Adam couldn’t speak, but his head bobbed up and down. I took off down the aisle carrying the empty glass with me and at the far end of the ward sat a pitcher of water. I could only hope it was fresh and would settle his cough like it had last time around.

I rushed back and handed Adam the glass. He drank. The cough was brought to an end, and he leaned his head back against pillows propped up behind him. He looked exhausted.

The doctor stood next to the bed with another glass although his water looked chalky, and I knew he’d already mixed in some sleeping powders for Adam. “He’ll rest easy now, Mr. Cartwright.”

“Thanks, Doc.” Adam looked up. His face was pale and his eyes were barely open. He looked miserable. In our household, it was usually me in the sickbed, not my brother so this was a complete turnabout for the two of us. “I’ll be back tomorrow. You sleep now.”

Abby also stood when the doctor arrived. I placed my hand on the small of her back and guided her out of the ward. Again, the simple touch, the closeness of a woman. Was it this young lady or was it the fact that it had been so long? I didn’t even know.

We walked through the front door of the hospital and stepped onto the sidewalk below. “Do you live far from here?”

“Not really,” she said. “Just a few blocks.”

“Well, you can’t walk alone in the dark. Shall I get you a cab?”

“I’d much rather walk, Joe.”

“Then I’ll walk with you.”

She smiled up at me. “Thank you.” The night air was pleasant, and after being on the stage until noon today, and then in hospitals and police stations most of the afternoon, I was more than happy to be outside.

I took a deep breath. “I love the smell of salt air.”

“I don’t notice it anymore.”

“How long have you lived here?”

“I moved out here shortly after Jackson had his business up and running, and he knew he would be staying for the long haul. There wasn’t much reason for me to stay in Boston. I like it here. It feels like home now.”

“It’s a great city. I’m sure you’ll be happy here for a long time.”

“Well, right now I’m out of a job. I was a secretary for Jackson and your brother so I don’t exactly know what’s—” Sobbing, she turned her back to me.

“Abby. What can I do to help?”

She looked so sad, so fragile. “Find my brother,” she said.

We continued walking but slower until we made it to her flat, a long row of houses with brackets holding up flat roofs. Maybe that’s where they got the name “flat.” They were very different than what I was used to but I liked all the various styles, one attached to another. It was unique.

“So you have neighbors on either side?”

“Yes.”

I guess my question seemed odd to her. I wasn’t a city boy and I was just trying to learn the ropes. “Kind of like a boarding house but you each have a separate front door, right?”

“Sort of, but everyone has their own parlor and water closet too. Nothing is shared like a boarding house.”

“I see.” I didn’t expect her to invite me in even though I was dying to see what a flat looked like inside, but it wouldn’t have been proper if she had, so I waited until she unlocked her front door, and I said goodnight.

“Thanks for walking me home, Joe.”

“My pleasure.” I tipped my hat and turned to leave. I figured our paths would cross again, especially if I did as she asked and looked for her brother, that’s if he didn’t find me first.

I had a long walk back to The Majestic, and I wondered if Adam lived in a flat too, and would I pass it along the way? The night air was balmy and the lingering smell of the sea made it an enjoyable walk even if my boots were undeniably made for riding, not walking.

It had been an exhausting day and I fell into bed as soon as I got to my room, realizing a little too late, I hadn’t eaten since breakfast at the way station early this morning. My stomach growled but I was too tired to do anything about it. Besides, who would be serving food at this time of night?

I’d packed clean shirts and trousers, but I’d forgotten a nightshirt. I thought about the fire and kept my long johns on, pulled the blanket up over my shoulders, and within minutes, I was fast asleep.

Steely gray clouds draped low to the ground as I walked to the telegraph office before stopping for breakfast. Pa would be beside himself since I hadn’t sent a message off yesterday. There really wasn’t too much I could say, not really knowing Adam’s condition or when he would be released to go home, but anything was better than nothing as far as Pa, or poor Hoss, was concerned.

I found a small café on the way to the hospital and stopped in for a bite to eat before seeing Adam. “I’ll have steak and eggs, ma’am, and potatoes and gravy, with a side of biscuits, oh and if you have any fresh fruit—” Her eyes widened and I wondered if I’d said something wrong. “Or—or maybe you could suggest something else.”

“Oh no, sir, coming right up.”

“Thank you.”

I’d picked up a copy of the San Francisco Chronicle. I had time to glance at the headlines while I waited for my breakfast, then I’d take it to Adam, knowing he’d read cover to cover, every word printed on every single page.

Breakfast was served in a matter of minutes, and I folded the newspaper and dug into my meal, which the young lady brought on two separate plates. I was starving, and this was food fit for a king. After mopping up the last speck of gravy with my biscuit and polishing off the last of my coffee, I reached inside my jacket for my wallet.

The young lady, dressed smartly, although her apron covered most of her dress, came and stood next to my table. “I didn’t think anyone could eat that much food,” she said.

“You haven’t met my big brother, Ma’am. This is just an appetizer for him.”

“Oh my.”

I smiled and handed her the price of the meal and a little extra. “Thank you, Ma’am. You have a nice day.”

“You too, Mr.—”

“Cartwright, Joe Cartwright.”

“Kathryn Lemont,” she said. “My father owns the restaurant and most people call me Kate. Mr. Cartwright?”

“Yes.”

“Are you any relation to Adam Cartwright?”

“Yeah, he’s my brother. Why?”

“I heard about the fire. Is he all right?”

“Yes, Ma’am—or he will be. Do you know my brother?” That was a dumb question. Of course, she did.

“Adam and Mr. Collier used to come in for breakfast most mornings, and then during the last few weeks it was just your brother who came by.”

I noticed her use of Adam’s first name. I wasn’t born yesterday. I’d heard it plain and clear. The food was delicious but it was more than knowing Adam “I could tell him you send your best, that’s if you—”

“That would be nice, Mr. Cartwright.”

“Just Joe, Ma’am.” I tipped my hat.

She smiled. “It was nice to meet you, Joe.”

I was off to the hospital with new little tidbits of my brother’s personal life swirling around in my head. I didn’t have anything for Adam except the newspaper and, of course, a friendly greeting from Kate. What a lovely lady she was, but getting Adam to open up, to tell me if there was a little romance between the two wouldn’t be high on his list.

I needed to see what else Adam might need, like maybe some clothes if his had been ruined in the fire. The beard was new, but knowing my brother, it probably just grew because he’d been a week without a razor. Heck, I could probably still go a week and no one could tell the difference.

No one was watching the front desk so I wandered back to the ward, hoping I wasn’t breaking any hospital rules. Adam was sitting up with his hands in his lap, looking as bored as I would’ve been had our situations been reversed.

“Hey, brother,” I said.

“Oh, good, you brought the paper.”

“Is that all I’m good for, a delivery boy?” My brother chuckled slightly and I waited for the coughing attack, but it didn’t come. “Hey, no cough.”

“So far, so good,” he said. I sat on the edge of the bed while Adam glanced at the front-page headlines then he laid the paper aside. “Doctor Mills was in earlier, and he says I can go home tomorrow now that you’re here to nurse me back to health.”

“Nurse? You wanna rephrase that? You know I ain’t about to wear one of those hats with wings.”

“I’m sorry—how about the caretaker?”

“That’s better.”

“So, do you mind giving up your fancy hotel and staying with me for a few days? It won’t be quite as comfortable. I only have one bed.”

“Do you live in a flat?”

“Yes, why?”

“Just wondered.”

Doctor Mills was tending to one of the other men in the ward and he’d glanced my way when I’d walked in. When he finished with his patient, he walked down the narrow aisle and gave me a friendly greeting. “Good to see you, Mr. Cartwright.”

“I hear you’re letting the old man out tomorrow.”

“Old man?”

“Old,” I repeated. “It’ll take a lot of babying on my part to get him back on his feet again.” My brother rolled his eyes but didn’t feel the need to comment. “So, you better give both of us instructions for his care because he won’t listen to a thing I say.”

“I think you have this a bit backward, little brother. You’ve always been the one who won’t follow doctor’s orders, not me.”

The doctor smiled. “Not many instructions except to lay low for the next week or so. I suggest you take a cab home and not try to walk these streets for a while. Your lungs are still healing, as are the burns so I wouldn’t rush things. Take it slow and easy.”

“That I can do, Doctor.”

“And I’ll make sure he does.”

“Very good,” Mills said. “I’ll send home some extra dressings for the burns and release you tomorrow morning.”

I sat back down on the bed when the doctor was finished examining Adam. It didn’t take long; he’d fixed his stethoscope in his ears, listened to my brother’s lungs, and said, “Better,” and that was it. He moved on to the next man across the aisle.

I didn’t know what all Adam knew about the fire or whether he had any idea where Jackson would be. Had he been told anything? Since Jackson wasn’t a patient in the ward, did he think his friend had died in the fire?

“Well,” Adam said, crossing his arms over his chest. “What are your plans for today?”

“I’m not sure. Tell me what you remember about the fire.”

He blew out a long breath. “Not much, Joe.”

“But what—”

Adam flattened his palms against the mattress, pushing himself up a little taller in the bed. “I was working late that night. Jackson and I had a deadline to meet, but he said he’d promised Annabelle dinner out, so I told him to go ahead. I would finish up. It must have been a couple of hours after he left when the fire broke out.”

I saw a look—anxious, maybe frightened—a look I’d never seen on my brother’s face before as he relived the events of that night. “Anything else?”

“The office burned fast, much too fast. I rolled up my drawings and the blueprints I was working on, and ran towards the office door. I was on the second floor, where we’d designed long, built-in tables along each wall so we could lay everything out and not have to gather up our drawings and put them away at the end of the day. We can have several projects going at once that way.”

“Makes sense. Always knew you were the smart one.”

“Yes, well, I’ll admit it was very efficient,” he said.

Adam was proud of his work and the way the office had been set up. My guess was it had been his idea to do things this way, but while I was thinking of how hard my brother had worked to make C and C a success, he was recalling the rest of the night.

“Something fell before I could get out the door, knocked me out—a beam, I suppose—a ceiling beam. I never made it—”

“Is that all you remember?”

“Yeah, just about, although—”

“What?”

“I could swear I saw someone. The smoke was thick. I’m just not sure what or who might’ve—”

His voice dropped off. I knew Adam was thinking hard, trying to remember. Lines etched his forehead. I didn’t know whether to tell him what I’d heard from Max O’Hara or let him try to remember on his own. Nothing had been proven so maybe it was better left unsaid.

“Has Jackson been in to see you?”

“To tell you the truth, Joe, you’re the first person I remember being here. The doctors had me on so much medication, I don’t remember much at all. Abigail was here with you yesterday, right?”

“Yeah. I met her at the front desk; we came in together.”

“Okay, at least I’m not losing my mind.”

“What?”

Adam shook his head. “I thought I was for a while—dreams—no nightmares,” he said with a slight grimace. “Now I know what you’ve gone through all these years, Joe, fighting the unknown and coming out the loser.”

I started to smile, but nightmares were nothing to smile about. “Tell me about the dreams,” I said.

“No,” Adam said. “They were just dreams.”

“Pa used to try to get me to remember. Most times I couldn’t but if you could—”

“If I could remember, I don’t think it would serve any purpose. Anyway, I can’t remember, so let’s drop it.”

“Okay. But if you do—”

“You’ll be the first to know.”

“Good. It’s settled.” If Adam could remember anything, it would help everyone understand what happened that night.

“I need you to do me a favor, Joe.”

“Sure, anything.”

Adam reached under his pillow and pulled out a small bag. Inside were his wallet and key to his house. “I need clothes,” he said, handing me the key and telling me his address along with directions on how to get there from here. “I seem to only have this hospital nightshirt and I don’t think the people of San Francisco want to see me walking the streets in this get-up.”

“You ain’t doing no walking anyway, big brother, but I will be glad to bring you some fresh clothes.”

The day was still young, and I’d left Adam to sleep before his trip home tomorrow. I wasn’t at all certain what I needed to do. I was anxious to see where Adam lived so that was first on my list. I left the hospital and walked down to The Majestic, checked out, and then with carpetbag in hand, I walked a mile or so to his flat.

Adam’s home had the same flat roof just like I figured it would, but it also had a flat front. It was like a straight up-and-down rectangle with neighbors on either side. I climbed the six stairs from street level and unlocked the front door, which had an elegant design etched into the frosted-glass window.

The house was narrow with a stairway along one wall. I carried my satchel and started up the first flight of stairs. This set led up to Adam’s bedroom, and then from the second floor, another set of stairs led to a small drawing room or maybe it was used for an attic. Adam didn’t have much in the way of furniture so the third floor was nearly empty and I figured it was a perfect place for me to camp out while I was here.

I suppose this was city life and maybe that’s what my brother liked. I wouldn’t last more than a single day in a place like this. I needed space around me and already, I felt like I needed to get back outside. I looked from one wall to the other thinking if Hoss was standing here with his arms spread out wide; I bet he could almost touch either side.

I stood in front of Adam’s wardrobe picking out an assortment of clothing, shirts, trousers, vest and jacket, clean long johns, and socks. I dumped the clothes from my small satchel on the floor of the attic, folded Adam’s, and then stacked them neatly inside.

I needed to head back to the hospital, but there was one more thing I needed to do before I took off walking again. I sat down on the wooden seat and after I finished my business, I reached up and pulled the chain. Water swished down the long brass pipe and the deed was done. We needed to modernize the Ponderosa.

I’d passed a burned-out shell of a building, and the one adjacent was nearly consumed too, on the way to Adam’s flat. I could only assume that’s what was left of Collier and Cartwright. I should have asked Adam for the address but it was the only blackened building close by so it had to be the one. Limestone blocks still stood in place so maybe there was a chance of rebuilding.

Realizing I should send off another telegram to Pa, telling him Adam would be coming home tomorrow, I chugged along, bag in hand. When I arrived, I handed the clerk Adam’s address and asked that any wires addressed to Cartwright be delivered there. I left a deposit and then headed back down the hill to the hospital. Life was sure easier on the back of a horse.

By the time I reached the hospital with my brother’s clothes, I knew I had worn blisters on both feet. This walking all day was for the birds. I plopped down on Adam’s bed and ran my hand through my sweaty hair. “I’m dead on my feet, Adam.”

He laughed. I didn’t think it was that funny. I’d been up and down stairs and up and down hills—heck there was nothing flat in this entire city. I was used to mountains and valleys but this was ridiculous.

“Tomorrow, I’ll show you an easier way to get around,” he said.

“This here’s your clothes.” I sat the bag on the bed and Adam started going through the clothing I’d brought.

“Boots?”

I let out a long sigh. I sure as heck wasn’t making that same trip again today. “Tomorrow.”

Adam looked up and I realized Doctor Mills was standing at the foot of his bed. “Since you have a suit of clothes, you might as well get on out of here, Mr. Cartwright. I don’t think another few hours are going to make much of a difference.”

“Really?” I said. “You okay with that, brother?”

“I can’t leave without boots, Joe.”

“Who cares? You ain’t walking anywhere anyway, right, Doc?”

“That’s right.”

“Come on, Adam, let’s get the heck outta here,” I said. “No offense, Doc.”

“None taken,” Mills said with a smile. “My only office is here in the hospital, Mr. Cartwright. I’d like you to stop back by in a week and let me check your breathing once more.”

“I guess that’s it then,” Adam said, sitting up even taller and extending his hand to the doctor. “Thank you for everything.”

As soon as Adam dressed, minus a pair of boots, and lucky for me that mine were too small or he would have demanded I hand them over, we walked out the front door of the building. As I’d helped him dress, I noticed how many bandages he had on his legs and his back. “Guess I have to change all these dressings for you, don’t I, Adam?”

“Yes, you do. You see, Joe, I can’t reach my back, although—”

“Okay, okay, I get the picture,” I interrupted before he made fools of us both in front of the other men in the ward.

He held onto my arm and I kept the pace slow. “There’s a Hansom. Hail him, Joe.” The horse-drawn carriage stopped right in front of us. After helping Adam in, and realizing just how sore and fragile he was, I climbed in and sat next to him. I gave the driver the address and we were on our way.

“See, big brother, boots weren’t necessary at all.” I failed to get a response.

The driver stopped in front of Adam’s flat. I watched the expression on my brother’s face as he contemplated the six steps up to his front door. This must seem like a mountain to him with his lungs messed up like they were. “Come on, take my arm.”

Reaching for the key I still had in my pocket, I unlocked the door and then guided him to the first chair I saw in his parlor, the one closest to the door. I barely got him seated before the coughing began. “You rest here a minute. I’ll get you a drink.” I raced toward the kitchen.

Adam sipped the water slowly until the glass was empty and the cough eventually stopped. “Think you can make it upstairs to lie down?”

“Not right now, Joe,” he said, still laboring to breathe.

My brother would need me close by, day and night, at least for the week to come. If I planned to leave and tried to do anything like go to the market or grab a newspaper, I was scared he’d start that dang cough and not be able to stop. I needed a backup person, someone I could trust, but I knew no one.

Nothing would have to be decided today, but either Pa would have to come out, or maybe—Abby—that might work. She mentioned she was without a job, and I’d rather pay someone I could trust rather than a total stranger.

The rest of the day went as well as could be expected. Doctor Mills had sent some powders home with us in case Adam had a rough go of it. I tried to convince him it would be to his benefit to let me mix some up, but he refused, saying they didn’t make things better, only different. I tended to agree but I didn’t let on.

There wasn’t much in the house to eat. I threw away a couple of rotten bananas and some moldy bread but there were two decent-looking apples. I cut one up for Adam, hoping he wouldn’t choke or start coughing again and took the other for myself. I guess this would have to be our supper tonight.

I moved Adam to the sofa. It was larger and a bit more comfortable than the small chair. He leaned his head back and steadied his breathing. Just eating the apple seemed to wear him out. “We need to talk, Adam.” I didn’t want him to fall asleep just yet.

His eyes were closed and he was in no hurry to open them and look at me. “About what?”

“About your friend Jackson starting the fire.”

It took a minute to sink in. His eyes remained closed, but when he answered me, it was that sarcastic, mocking tone. “Right—and who or what gave you that idea?”

“It’s not exactly me who thinks it, Adam, it’s Max O’Hara, the detective who’s taken on the case.”

That seemed to get his attention, and although his head didn’t move an inch, his eyes shifted in my direction. “You’re telling me this detective, whoever thinks my partner, my best friend for twenty years, started the fire, ruined our business, and tried to kill me in the process. Do I have that right, Joe?”

He made it through his discourse without coughing and I was glad about that but—“There’s more, Adam.”

“Do tell.” With his eyes closed again, I couldn’t help but notice a muscle in his jaw clenching and unclenching as he tried to process what I’d said. “Well?”

“Okay, here goes, brother. The man who tried to kill me and Tim up at that line shack was—well, he was Jackson’s father. His name was Harold Collier. I killed that man, Adam. I killed Jackson and Abby’s father.”

Adam needed another minute to absorb the new information. I watched his eyelids move, darting, searching for meaning and understanding. He was listening but he remained silent so I continued.

“Jackson sent out letters, Adam. He eventually found out it was me who killed the father he believed died over thirty years ago. O’Hara, the detective, and I think he may have set that fire to get back at me by killing you. But then he may have had second thoughts and run back into the burning building to drag you—”

“Wait—wait a minute!” My brother came alive. He sat up taller—he leaned forward, rested his elbows on his knees, and rubbed his temples with the tips of his fingers, trying his best to comprehend. “How do you—where did you come by all this information?”

I knew this would be tough to understand but it had to be said. “Pa wrote to the warden at the NSP. He had suspicions about—well, that there might be some connection between—”

“And neither of you thought I should know about this. This was all one big secret?”

Now he was mad, madder’n a hornet. “It wasn’t meant to be a secret, Adam. Pa and I decided not to interfere with—”

“Interfere?” Adam bolted up and started pacing the small parlor like a bull with a spear embedded in either side. “So what you’re telling me is that the man you’d been cellmates with, the man you eventually killed, the man who tried to kill you, and Tim Wilson is Jackson Collier’s father?”

“Adam—” He held the palm of his hand out to stop me from saying anything more.

“Then,” he said, glaring at me with eyes that, I swear, could have shot flames, “you and Pa decide to tell me nothing about it.”

I stood from my chair none too soon. My brother was bent in half, coughing so badly I had to hold him steady, afraid he might injure himself without my help. “Come on, Adam, sit down.”

He was beyond mad. He tried to push me away but I held tight until I had him settled back on the chair. The sudden attack finally calmed down enough that he was able to breathe evenly again.

“I’m sorry,” I said when he was able to listen. “We were wrong. You should have been told.”

His resulting silence led me to believe he was still fuming but not able to rant—to continue his angry outburst for fear of a second attack. We would talk more about it when he was able but for now, my brother and I sat in silence.

Finally, the silence was broken. “I’m tired, Joe. Will you help me upstairs?”

Together, we attempted the slow trek up the long flight of stairs to Adam’s bedroom. I stopped several times, praying the cough wouldn’t return. I wondered if we hadn’t left the hospital too soon. This was Adam’s first day out of bed and it was almost more than he could endure, moving and climbing around like this.

Once I had a nightshirt on him and he was settled in bed, I told him he was going to stay there for the entire week and there’d be no argument about it. He didn’t argue and that only made it worse, knowing how much pleasure he found in disagreeing with me. I knew he was exhausted but it was the new information causing the silence.

His eyes were already closed when I leaned in, pulling the quilt up over his chest. I went back downstairs to bring up a chair. Tonight, at least, I would be sleeping in the same room with my brother.

Morning came, and I felt a hundred years old. I rolled my head and rotated my shoulders before I even ventured out of the uncomfortable chair. On the plus side, the water closet was just a few feet away and not out behind the house.

“Good morning,” I said, noticing my brother’s eyes staring at mine.

“Morning, Joe.”

“You feelin’ okay? Need to sit up for a while?”

“I need to go—”

“That can be arranged.” Unlike my father, I’d never played nursemaid before, but I remembered how Pa always had a cheery attitude and would try his best to cheer his patient up too. I could only try to emulate my father and be as optimistic as possible. “Up and at ‘em, brother,” I said with a little too much enthusiasm. I received a strange look from my brother. “Come on,” I said, trying to lift Adam from the bed.

“Ease up, Joe.”

“Okay.” I guess you had to be Pa.

The water closet was next to Adam’s bedroom so we didn’t have to travel far. He also had a sink and a claw-foot bathtub with a drain, just like the fancy hotels. I shut the door behind me, allowing Adam some privacy. If he called for me, I would be just outside, waiting.

I found a robe and slippers and had them ready and waiting. I hadn’t done anything last night but slip off my boots so I was already dressed and ready to go, even though I knew the farthest I was going today was downstairs.

“I can make us some breakfast,” I said, but sadly remembered what I’d thrown out the night before and thought there wasn’t much left after that.

“I don’t know what I have. You’ll have to look and see. I know I have coffee, though.”

“Coffee it is.” When Adam was settled in the chair I’d used for a bed, I headed downstairs to the kitchen. I could tell already that this was going to be a very long day.

We drank black coffee and I opened a can of peaches—the last morsel of food Adam had in the house. I would need to go out and get groceries if we wanted another meal. Adam had an icebox in his kitchen, but the ice had long since melted and I didn’t trust what was in there. He explained that ice was delivered once a week, early on Thursday mornings, and since he hadn’t been here, it had more than likely melted on the front stoop.

Water still had to be heated for bathing, but at least it drained out from the upstairs closet and didn’t have to be carried back down. Adam had a fireplace in his bedroom and he said he normally heated the water there. I told him I’d help him if he wanted to clean up some but he declined the offer. He was too tired to care.

“Is there a market nearby? We’re going to need some food before long, Adam.”

“I suppose we will. We can’t live on peaches forever, can we?”

“That was your last can, big brother, so no, we can’t.”

“I usually stop for breakfast,” Adam said, then stopped to refill his lungs. “A little place—”

“Called Le Café?” I grinned at the look on my brother’s face. “A little place where a young lady named Kate Lamont works, right?”

“Just how in the world—”

“I get hungry too, older brother. By the way, Kate sends her regards. She heard about the fire and was worried about you.”

“You’ve been here less than two days, Joe. What are the odds?”

I shrugged my shoulders. Adam was struggling to talk and his hoarse, croaky voice needed rest just as he did. “Let me change the bandages and let’s get you back in bed before you fall outta that chair.”

There was no argument. I had him turn around in the chair, draping his arms over the back so I could tend his burns properly. I removed the strips the doctor had wrapped around Adam’s chest and the smaller pads covering the burns. I could see the inflamed tissue, the red swollen patches where the beam had fallen across his back.

“This is gonna hurt.” There were no words: he only nodded his head. I dabbed on the burning alcohol and my brother jerked, arching his back away from my touch. I’m sorry, Adam, I’m sorry.”

He took a deep breath and I continued, knowing every time I pressed the cloth to his back I was causing him pain. The worst part was over, and I smoothed a generous amount of salve over the reddened area before I bandaged the wounds. But we weren’t finished yet; there were still his legs to tend with.

“You wanna lie on the bed and I’ll check your legs?”

When my brother stood from the chair; the pain he was in was more visible than before. The tear tracks on his face; the way he stood, not able to straighten to full height. I wrapped my arm around his waist and guided him to the bed, knowing more had to be done.

Four places on the back of his legs still needed tending and when I hesitated to continue, knowing the agony Adam was in, my brother spoke up. “Just get it over with, Joe.”

I did the same as I’d done with his back and by the time I was finished, Adam was exhausted and falling asleep. I pulled the quilt up over his shoulders. “Rest easy,” I said, although he may have already drifted off.

Adam was settled for now so I picked up the soiled bandages and headed downstairs to wash up our breakfast dishes. I’d just put the water on to boil when there was a knock at the front door. A young boy stood outside.

“Telegram for Joe Cartwright, sir.” I handed him a nickel and tore open the envelope.

“`

Joseph Cartwright, SF, California (stop)

Leaving on today’s stage (stop)

Leaving Hoss in charge of ranch (stop)

Ben Cartwright, Virginia City, Nevada (stop)

“`

By the time I ran back up the stairs to tell Adam, all I could hear was a gentle snore. I’d said very little in my telegram. I didn’t want Pa to worry unnecessarily, but we were talking about my father and worry was his middle name. I’m surprised he’d allowed me to come in the first place, knowing he’d never be able to sit home for long when one of his sons was ill.

Finding Jackson, as Abby Collier had asked of me, would have to wait until who knows when but getting food into the house was a priority. I stepped out the front door and looked up and down the cobblestone street where row after row of flats stood as far as I could see. No mercantile or cafés in sight. I’d have to wait till Adam woke and then maybe I could risk going out.

I sat in the parlor twiddling my thumbs. I had nothing to do but wait for Adam and wait for Pa. I finally took the time to notice what was actually in the room.

My brother had bought himself a large oil painting of a schooner, and it hung on the wall above the sofa. With its tall masts and huge, billowing sails, I could almost imagine it bucking and skipping over every wave, making its way through rough, white-capped seas. This ship was named The Weymouth, built in 1860. I wondered how many voyages it had made over the last ten or so years.

Sailing was my brother’s heritage; his grandfather’s life and our father took a stab at life at sea. I suppose Adam might have followed suit if he hadn’t studied architecture and knew in his heart he needed to put all those years of education to use.

That sure wasn’t the life for me. I was as good as gold with both feet planted on the ground. The highest I cared to be was on top of my horse. You’d never catch me climbing tall masts for a living.

I picked up a gold-framed picture from the side table next to me. It was an old tintype of Pa, sitting in his chair with the three of us surrounding him. I remembered the day the picture was taken, so long ago.

It was a Saturday. Pa had us dress in our finest attire, and it wasn’t me or Adam who primped in front of the mirror the longest that day, it was Hoss. This funny little man, who’d come from St. Louis to make his fortune in the West, came to the house to take our picture. We didn’t dare smile; in fact, we all looked stone-cold sober, or dead, if you want to know the truth, and between Hoss and me, neither of us could keep from pinching each other and carrying on throughout the entire process. Adam rolled his eyes at our harebrained shenanigans and Pa was constantly clearing his throat, trying to get us to behave and get the show on the road.

I ran my finger over the glass—Pa in his black suit and silver vest, Adam always in black, and me in my brown, Sunday suit and poor Hoss—the last thing he wanted to do in life was dress up fancy, but boy—didn’t we all look sharp that day.

I couldn’t help but think back as I stared at the four younger faces, how different life was, how simple life seemed. I was fresh out of Miss Abigail’s schoolhouse—my first year as a full-time—full-fledged—ranch hand along with full pay. The four of us, four Cartwright men protecting what was ours, protecting the land.

That was long before Grace Monroe and her partner Richard Owens set foot in Virginia City—long before Adam met the lovely young lady, fell in love, and planned to marry. Long before I spent eight years of my own damn life locked in a cell with . . .

I set the picture back on the table. I couldn’t even have a decent memory without the likes of Owens and Collier destroying everything. I glanced once more at the tintype. I studied the young boy just starting out in life, wanting to be a man just like his older brothers and Pa—so eager—so full of life.

This whole mess, this ongoing chain of events should be settled by now. I’d paid a debt; I’d lost eight years of my life and still, my life and now Adam’s was in jeopardy. The chaos needed to end—this craziness that now included my brother needed to end once and for all.

I lay my head on the back of the emerald-green sofa to rest my eyes. I hadn’t slept much last night, and maybe I’d nap while Adam did the same. Within minutes, I was sound asleep.

A loud banging noise woke me, ending my bizarre and bloody dream. Trapped alongside the bawling of dying cattle grouped tightly together before being slaughtered, I felt terrified and disoriented as my eyes flew open and I quickly scanned the unfamiliar room.

Someone was knocking at the front door. With my heart still racing, I realized it was only a dream. I ran my fingers through my hair as I stood up from the sofa, quickly trying to make sense of the awful nightmare before I opened the door.

“Abby,” I said, surprised to see her standing on the front stoop.

“Hello, Joe.”

“Come in—please.” I took hold of her hand and practically dragged her into the house. “I’m really glad to see you.”

“Then I’m glad I stopped by. Dr. Mills told me Adam had been released, and I assumed you’d both come back here so he could recuperate.”

“That’s exactly what we did but Adam’s sleeping right now, so—”

“I came to see you, Joe. I thought you might need some help, you know, with Adam and all.”

“You have no clue,” I said, laughing. “Come in. I’ll make us some coffee.”

“Would you like me to, I mean—”

“The kitchen is all yours,” I said, waving my hand in that direction. “I only drink my own coffee out of desperation so I’d be beholdin’ if you’d do the honors.”

Abby removed her frilly hat and matching rust-colored cape and headed straight for the kitchen. I followed her and re-kindled the fire in the stove. She took one look at the shelves and turned back to me. “There’s nothing here to eat, Joe.”

“Well,” I said, “that would be the next problem—groceries.”

“Don’t give it a second thought,” she said. “Do you want to go to the market or shall I? One of us needs to stay here with Adam.”

“Um, I don’t mind going if you’ll stay here with my brother while I’m gone. Of course, you’ll have to point me in the right direction. I don’t know my way around the city.”

“Then let me go and I’ll come back and cook enough food to last the both of you a couple of days.”

“You’d do that?”

“I’d be more than happy to.”

“It’s settled then. You can go, and I’ll give you enough money for whatever you think we need.”

“You can … just in case, but I’m sure your brother has an account at the nearest market.”

We sat and drank our coffee while Abby made out a list of things Adam and I liked to eat and then she stood up to leave. “Adam will be grateful, Abby,” I said. “And now, neither of us will starve to death either. I wasn’t quite sure how I was going to manage around here alone.”

“Don’t you worry about anything, Joe. I’m happy to help.” She stood on tiptoes and kissed me on the cheek. I hate to admit how good it felt not to be shunned by a woman. I wasn’t sure how much she knew about my past. I didn’t know what Jackson had told her or even what he knew himself.

“Wait just a minute,” I said. I’ll be right back.” My jacket was in Adam’s room where I’d left it last night. I ran up the stairs and grabbed my wallet from the inner pocket. Adam was still sleeping but he’d be starving when he woke up so this was working out well.

“Here you go,” I said, handing her a couple of notes. “You don’t know how much I appreciate this, Abby.”

“It’s my pleasure.”

I watched her walk out the door and down the steps. She turned back toward me, smiling as she tossed her hand in the air and waved. I waved back. She was such a pretty girl with sandy blond hair and eyes as blue as Hoss’. She was dressed more casually today than when I’d met her at the hospital. She had her hair pulled back at the nape of her neck with a blue, satin ribbon rather than piled on top of her head like most of the city women I’d seen. I knew she was a few years older than I, but she looked so much younger today than she had at the hospital; I was anxious for her to return.

And return she did. I’d been watching out the front window like a nervous kid. Adam had woken up while she was gone, and I explained she had stopped by and had gone to the market, and then she was going to cook something for us to eat. He seemed pleased, but still, I wasn’t about to let him out of that bed.

“I’ll expect you to behave yourself, Joe. I don’t have the energy to chaperone the two of you.”

“Yeah, right, Adam. I barely know the girl. Just what do you think’s gonna happen?”

“I lived with you for a lot of years, younger brother, and I know how just the sight of a pretty girl turns your head, so don’t give me any of that ‘nothing’s gonna happen’ line because I ain’t buyin’.”

“You don’t have to worry this time,” I said, although even as he made his observation clear, I was already opening myself up to her. I longed for flirtatious banter. Maybe it was her scent or the way she moved, but like Adam said and I didn’t admit, I was interested.

When the cab pulled up outside, I ran out to carry in the supplies. I think she bought out the store after she realized we had nothing and that the two of us would be cooped up here for at least a week. She was even able to get a block of ice wrapped in burlap, which I slung over my shoulder and carried, along with a wooden crate filled to the top with meat, various canned goods, and fresh produce.

I ran back out for another crate, paid the driver, and when I returned to the house, I found Abby in the kitchen already starting to put things away. She’d left her short jacket and her hat draped over the chair and had rolled up her sleeves. This woman meant business.

“Can I help?”

“Can you peel?”

“Can I peel?” I rolled up my shirtsleeves. “Peeling potatoes for our cook was one of my punishments when I was a kid.”

She smiled, then handed me a knife and a wooden cutting board and put me to work. Potatoes, carrots, turnips, and of course an onion, which I’d planned to save for last. “Get busy,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

She finished putting things away, keeping out a nice piece of meat, so I could rightly assume we were having beef stew. By the time she had the meat seared and ready to put in the oversized pot, my peeling and chopping were finished, even the onion—and yes, it brought tears to my eyes.

“All right,” she said. “Now it needs to cook.”

“You’re a lifesaver, Abby. I wasn’t sure we’d ever eat again.”

“How’s Adam doing?”

“He’s tired and sore. It’s gonna be a while yet before he’s up and around.”

I extended my elbow to her. “May I escort you out of the kitchen, ma’am?”

“Please,” she said, smiling up at me.

I wasn’t sure how much of this thing with her father would come between us but I did hope we could be friends. She hadn’t talked to O’Hara about the fire so she couldn’t begin to know what Jackson had in mind when he’d lit that match.

I led her into the parlor, and as soon as she was seated, she rolled down her sleeves and brushed back the wispy little blonde hairs that hung gracefully around her cheeks. “I seemed to have worked up quite a sweat in that kitchen, Joe. You’re seeing me at my worst.”

“I still like what I see.”

She started to make a face, but then the corners of her mouth turned up when she changed her mind and smiled. “Thank you,” she said.

We didn’t discuss her father or Jackson, and I was pleased about that. She asked about the Ponderosa and I told her everything I could think of but never brought up the time I’d spent away from home. I told her that my father was on his way here and when I thought he should arrive. She agreed with me that having Pa out here would help with Adam’s recovery.

We talked and laughed, and when I realized how long we’d sat there together, I had forgotten about Adam. “Will you excuse me a minute while I check on my brother—see if he needs anything?”

“Go ahead, Joe. I need to stir the stew.”

Adam was sitting up in bed reading one of the many books he’d had us ship out to him after he was settled. He had a least a hundred choices of leather-bound books shelved against his bedroom wall. “Shakespeare?”

“Melville.”

“Moby Dick?”

“That’s the one.”

“I thought I was the only one who liked that story.”

“Variety is the spice of life, Joe.”

“I guess so.”

He placed his finger between the pages to mark his place and set the book on his lap. “If you’ll help me get dressed, I think I’d like to come downstairs to eat supper rather than trying to manage up here.”

“You know Pa wouldn’t let you out of that bed, but I guess we could see how it goes.” He must be feeling better although I was still concerned about the number of stairs. “Supper won’t be ready for a while yet.”

“My stomach’s been growling ever since Abby put that piece of meat on to cook.”

“You knew she was here?”

“I may not be able to take a deep breath, Joe, but I’m not deaf and I still have a sense of smell.”

“Oh,” I studied Adam for a minute. “Why don’t we just put your dressing gown on instead of all those clothes?”

Adam seemed to be thinking it over while I waited at the foot of his bed. “That makes more sense, doesn’t it?”

“Sure be easier, brother, and you won’t be all worn out before we start down the stairs.”

“Okay,” Adam slipped his legs over the side of the bed. I reached for the gown I’d laid over the back of the chair and turned back quickly when I saw Adam wobble and grab hold of the edge of the bed.

I held him steady, realizing I should have acted more like Pa, refusing to let him out of bed. Descending the stairs in his weakened condition was a stupid idea. “You all right?”

“I am now.”

“Okay then, ready when you are.” We crossed the room slowly and then stood at the top of the stairs. “Two steps and then rest, Adam. We’re not in any hurry.”

“You’re the boss.” I almost laughed, but no use getting careless while steadying my brother on the stairs.

We all sat down in the kitchen for dinner. Adam and I both complimented Abby on the great meal. I think at this point we would have eaten just about anyone’s cooking but the meal she prepared was truly delicious.

When we’d finished, Adam held tightly to my arm and I led him to the sofa where I hoped he’d be more comfortable. I left him alone while Abby and I washed up the dinner dishes but he didn’t seem to mind. There was enough leftover stew for tomorrow’s lunch and she said she’d be back to fix supper tomorrow night so we wouldn’t starve to death before my father arrived.

“Why don’t you walk Abigail home, Joe? It’s just a few blocks from here and I’ll be fine by myself for a while.”

“I don’t know, Adam. I don’t think—”

“Don’t think, Joe—just do.”

“Okay, if you’re sure.”

“Go on, I’ll be fine.”

The three of us fell into a routine over the next few days. After I’d tended his wounds each morning, Adam felt the need to get dressed and come downstairs. The fear of infection seemed to be over so I’d quit the alcohol treatments and just covered the swollen areas with salve. Abby’s dinners must have given him the boost he needed so by the time Pa arrived, my brother and I had started taking short walks through the neighborhood.

Abby remained our cook—a godsend for the two of us—and she and I took turns running errands while the other stayed home with my brother. Still, the cough could be violent, but the attacks were becoming less frequent as days passed.

On the third or maybe fourth day, and before Abby’s arrival, Adam was feeling his old self again and he was starting to ask questions. The doc had sent pain medications home with us, but Adam had refused any of them so his head was clear and his body was beginning to heal. The stiffness was gone and he was moving more freely.

I’d made coffee, which Adam noted was finally becoming drinkable, and I scrambled some eggs for breakfast. I knew he was feeling better now that he was starting to strike out at me with his roundabout compliments.

“Joe?”

“Yeah—”

“As much as I hate to admit it, I’m having trouble putting together everything you told me the other day.”

“You mean about the fire and Jackson?”

“Yeah,” he said, letting out an exaggerated sigh. “Has Abby said anything? Does she know the detective claims Jackson may have started the fire?”

“She’s unaware, brother.” I divided the eggs onto two plates and set them on the table. “More coffee?”

“Yes, thanks.”

“She’s asked me to find Jackson for her,” I said. I filled our cups and sat down across from my brother.

“What?” he said in that long, drawn-out voice he sometimes uses, making one word sound like an entire sentence.